Rocket nozzles are crucial components that transform chemical energy into propulsive force for spacecraft.

These specialized devices are typically made through precision manufacturing techniques like computer-controlled machining, 3D printing, or casting. The nozzle shape is carefully designed to optimize thrust and efficiency.

Materials for rocket nozzles need to withstand extreme heat and pressure. Common choices include high-strength alloys, ceramics, and carbon-based composites.

The nozzle walls often contain cooling channels to prevent melting during operation. Some designs use ablative materials that slowly erode to carry heat away.

Nozzle production requires strict quality control to ensure proper performance. Manufacturers test for defects using x-rays, ultrasound, and other inspection methods.

The finished nozzles undergo rigorous testing to verify they can handle the harsh conditions of rocket flight. This attention to detail helps ensure safe and reliable space launches.

Fundamentals of Rocket Nozzle Function

Rocket nozzles play a crucial role in generating thrust and maximizing propulsion efficiency. They control the flow of hot exhaust gases to create the force that propels rockets forward.

Role of Nozzles in Rocket Propulsion

Rocket nozzles turn the high-pressure, high-temperature gases from combustion into useful thrust. They speed up and direct the flow of exhaust gases. This creates a pushing force on the rocket in the opposite direction.

The nozzle shape is key. It changes the pressure, temperature, and speed of the exhaust as it exits. A well-designed nozzle boosts the exit speed of gases. This increases thrust.

Nozzles also protect the rocket structure. They contain and guide the extreme heat and pressure from combustion.

Principles: Conservation of Mass and Momentum

Two main laws govern nozzle function: conservation of mass and momentum. These principles explain how nozzles create thrust.

Conservation of mass means the amount of propellant flowing through the nozzle stays the same. The mass flow rate is constant from the combustion chamber to the nozzle exit.

Conservation of momentum relates to Newton’s laws of motion. As exhaust gases speed up and exit the nozzle, they create an equal force pushing the rocket forward.

The change in exhaust speed leads to thrust. Faster-moving exhaust means more thrust. Nozzles are shaped to maximize this speed increase.

Convergent-Divergent (De Laval) Nozzle Dynamics

Most rocket engines use convergent-divergent nozzles, also called De Laval nozzles. These have a narrow throat between wide ends.

The converging section slows and compresses gases. At the throat, flow reaches sonic speed. The diverging part then expands and accelerates gases to supersonic speeds.

This design is efficient. It converts high pressure and temperature into high exhaust velocity. The expanding section allows gases to keep speeding up after reaching sonic speed.

Nozzle performance depends on the pressure difference between the chamber and outside air. Engineers adjust nozzle shape for different altitudes and ambient pressures.

Rocket Nozzle Design Considerations

Rocket nozzle design plays a key role in engine performance. Engineers must carefully consider several factors to create efficient nozzles that can withstand extreme conditions.

Throat and Divergent Section Design

The throat is the narrowest part of a rocket nozzle. It connects to the divergent section, which expands outward. The throat’s size affects the exhaust flow rate and pressure.

Engineers use convergent-divergent nozzle shapes. These speed up exhaust gases to supersonic speeds. The divergent section’s shape is crucial for thrust.

Nozzle length impacts efficiency. Longer nozzles can be more efficient but add weight. Designers must balance these factors.

Conical vs. Bell vs. Contour Nozzles

Conical nozzles have a simple, straight-sided shape. They’re easy to make but less efficient than other types.

Bell nozzles curve outward, like a bell. They’re more efficient and lighter than conical nozzles.

Contour nozzles have a carefully designed curved shape. They offer the highest efficiency but are complex to make.

Each type has pros and cons. Engineers choose based on the rocket’s needs and budget.

Materials and Heat Resistance

Rocket nozzles face extreme heat and pressure. Materials must withstand these harsh conditions.

Common materials include:

- Graphite: Good for high temperatures

- Phenolic: Used as a heat-resistant lining

- Metal alloys: Provide strength and heat resistance

Cooling systems help protect nozzles. Some use fuel to cool the nozzle before burning.

Designers may use different materials in various nozzle parts. This helps manage heat and stress in specific areas.

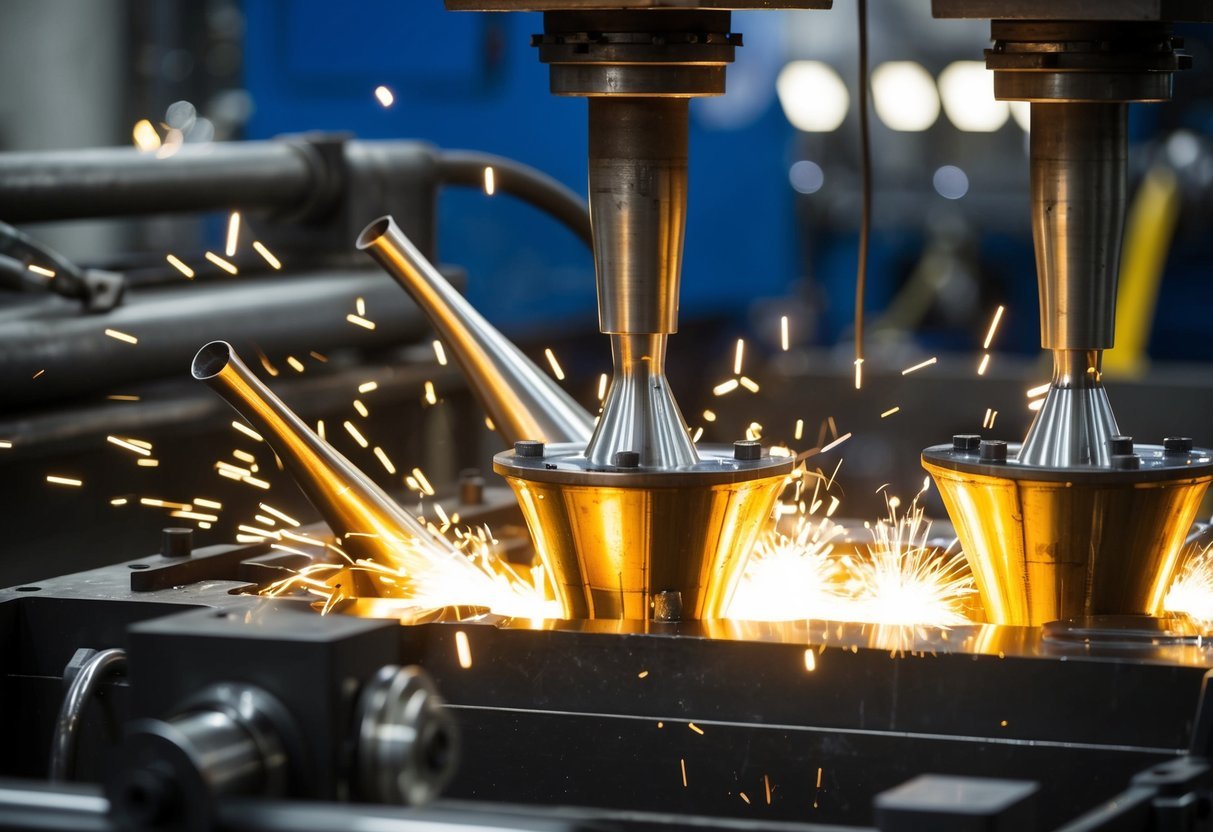

Manufacturing Techniques for Rocket Nozzles

Rocket nozzle production uses advanced methods to create strong, heat-resistant parts. Key steps include picking the right materials, making cooling systems, and careful testing.

Materials and Machining Processes

Rocket nozzles are made from tough metals like stainless steel or nickel alloys. These can handle extreme heat and pressure. The process starts with big metal blocks.

Machines called lathes shape these blocks. They spin the metal fast and cut it to the right size. This makes the basic nozzle shape.

Next, special tools carve channels into the nozzle walls. These channels are crucial for cooling. Welding or brazing joins different nozzle parts together.

Some companies use 3D printing for nozzles. This can make complex shapes faster than old methods.

Regenerative Cooling Systems

Regenerative cooling keeps nozzles from melting during use. It’s a smart way to use the rocket’s own fuel to cool the nozzle.

The process starts by making tiny channels in the nozzle walls. These channels form a maze-like pattern.

Cold fuel flows through these channels before it burns. This cools the nozzle and heats up the fuel at the same time. It’s a win-win!

Making these cooling systems is tricky. The channels must be the right size and shape. Even small mistakes can cause big problems.

Quality Assurance and Testing

Every nozzle goes through strict checks. This makes sure it’s safe and works well.

X-rays and ultrasound scans look for hidden flaws inside the metal. These tests can spot tiny cracks or weak spots.

Pressure tests check if the nozzle can handle the forces of a real launch. Water or gas is pumped through at high pressure.

The final test is a hot-fire. The nozzle is attached to a real rocket engine and fired up. This shows how it performs in action.

Only nozzles that pass all these tests are used on rockets. This helps keep launches safe and successful.

Performance and Efficiency Factors

Rocket nozzle design plays a crucial role in maximizing engine performance. Key factors include exhaust velocity, pressure ratios, and fuel efficiency. Precise engineering of these elements helps achieve optimal thrust and control.

Optimizing Exhaust Velocity and Pressure

Nozzle shape affects exhaust gas acceleration. A converging-diverging design creates supersonic flow. The throat constricts gas flow, while the expanding section accelerates it. This boosts exhaust velocity.

Exit pressure matching is vital. Ideally, nozzle exit pressure equals ambient pressure. This prevents energy loss from under or over-expansion. Adjustable nozzles can maintain ideal pressure ratios across flight regimes.

Expansion ratio impacts performance. Higher ratios increase exhaust velocity but may cause flow separation. Engineers balance these factors for each mission profile.

Specific Impulse and Fuel Efficiency

Specific impulse measures rocket efficiency. It represents thrust per unit of propellant flow rate. Higher specific impulse means better fuel economy.

Nozzle design affects specific impulse. Longer nozzles generally increase it by allowing more exhaust expansion. But they add weight, creating a trade-off.

Fuel and oxidizer choice also impact efficiency. Some propellants offer higher energy density. Nozzles must be optimized for the chosen propellant mix.

Cooling systems protect nozzles from extreme heat. Regenerative cooling uses fuel flow through nozzle walls. This preheats fuel and boosts efficiency.

Thrust Vector Control Techniques

Thrust vector control steers rockets by adjusting exhaust direction. Gimbaled nozzles tilt to change thrust angle. This method offers precise control but adds complexity.

Jet vanes deflect exhaust flow. Small panels in the nozzle exit create steering forces. They’re simple but reduce efficiency slightly.

Vernier engines provide small steering thrusts. These are separate, movable nozzles. They offer fine control without main engine gimbaling.

Fluid injection systems spray coolant into the nozzle. This creates asymmetric thrust for steering. It’s lightweight but less precise than other methods.

Rocket Nozzle Variants and Innovations

Rocket nozzles come in various designs to optimize performance across different flight conditions. New materials and manufacturing methods are expanding possibilities for nozzle construction.

Supersonic Nozzle Types

The de Laval nozzle is a common supersonic nozzle design. It has a converging section followed by a diverging section. This shape accelerates exhaust gases to supersonic speeds.

Overexpanded nozzles have a larger exit area optimized for high altitudes. They may experience flow separation at low altitudes. Underexpanded nozzles have a smaller exit area suited for low altitudes.

Bell nozzles have a curved contour that shortens overall length. Conical nozzles are simpler to make but less efficient. Aerospike nozzles use the atmosphere as part of the nozzle structure.

Advanced Concepts: Dual-Bell Nozzles

Dual-bell nozzles aim to improve efficiency across varied altitudes. They have two distinct bell shapes joined by an inflection point.

At low altitudes, flow separates at the inflection point. This creates a smaller effective area ratio. At higher altitudes, the flow expands to fill the entire nozzle.

This design provides good performance from sea level to vacuum. It avoids the efficiency losses of fixed-geometry nozzles across altitude ranges.

Alternative Propulsion Methods

Some rockets use solid propellants instead of liquid fuels. Solid rocket motors have simpler nozzles without cooling channels.

Hybrid rockets combine solid fuel with liquid oxidizer. Their nozzles must handle both hot gases and liquid injection.

Electric propulsion systems like ion engines use electromagnetic fields instead of thermal expansion. Their “nozzles” are grids that accelerate charged particles.

Nuclear thermal rockets heat propellant with a reactor. This allows simpler nozzle designs than chemical rockets.